How to Nourish Your Gut Microbiome After Antibiotics, Illness, or Procedures

The gut microbiota is vast and diverse, unique between individuals, and can fluctuate over time — especially during disease and early development but also through weight. Common causes of gut microbiome alteration are narrow- or broad-spectrum antibiotics, procedures such as colonoscopies, and illnesses such as Ulcerative Colitis (UC) or Irritable Bowel Disease (IBD).

There are as many bacterial cells in us as there are human cells, and they help control various processes ranging from inflammation to the development and treatment of cancer. They even affect the amount of energy obtained from foods we consume and perhaps even food cravings and mood stability. When our microbiome becomes unbalanced—often indicated when certain species or groups of bacteria become overly abundant—these functions can be disrupted, contributing to the development of a wide range of diseases or imbalances such as obesity, cancer, IBD, and many others.

Below is a guide to gradually balancing out the gut microbiota after or amidst such processes. As a nurse, I always suggest that you please consult your healthcare provider when undertaking any healing process. Many of these recommendations, such as herbs, may seem harmless but plant medicine is just that—medicine—and it can be powerful (many medications are derived from plants, such as antiarrythmics) and there are contraindications to certain remedies.

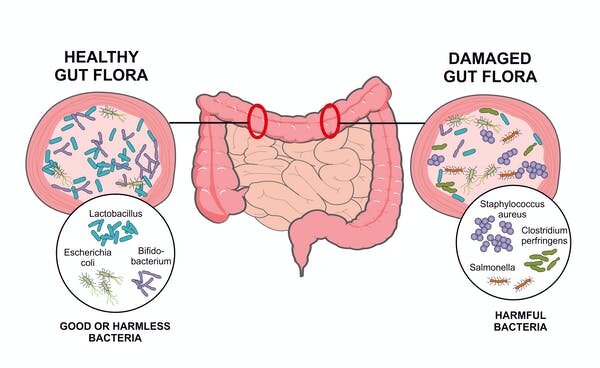

Our gut at all times has goo and bad bacteria; it’s rather a matter of whether the bad bacteria are overpopulating the good ones. There are even harmful bacteria that lay dormant in our guts that can be activated through illnesses or procedures that lessen our good bacteria.

Antibiotics or the wrong diet damage the good bacteria living in the gut and promote the growth of harmful bacteria. Soleil Nordic/Shutterstock.com

Probiotic & Synbiotic Foods and Supplements

Probiotic foods range from fermented dairy- or plant-based milk products like yoghurt or kefir; fermented vegetable products sauerkraut, kimchi, or any lacto-fermented vegetable; and beverages such water kefir, kombucha, and even wine, preferably natural wine (which also has a bitter component through alcohol that, in moderation, can assist in digestion).

I recommend food over supplementation of probiotics generally, especially with home-fermented foods as temperature can be regulated better than often the lack thereof with transportation of goods across states or even countries, which can kill most if not all the beneficial bacteria in the product. Making fermented vegetables at home is also cheaper as a head of cabbage costs $2 and all you need is a large jar. If this is not possible, the next best option if it’s viable for you, is getting fermented products that are from local companies, with which a growing number grocery stores partner up.

I also recommend consuming prebiotic foods, which are mostly fibers that are non-digestible food ingredients and beneficially affect the host’s health by selectively stimulating the growth and/or activity of some genera of microorganisms in the colon, generally lactobacilli and bifidobacteria (DeVrese and Schrezenmeir 2008)

Some of the sources of prebiotics include: soybeans, inulin sources (like Jerusalem artichoke, chicory roots etc.), raw oats that can be eaten as soaked overnight oats, unrefined barley (if not diagnosed with Celiac), yacon, non-digestible carbohydrates, and in particular non-digestible oligosaccharides. However, among prebiotics only bifidogenic, non-digestible oligosaccharides (particularly inulin, its hydrolysis product oligofructose, and (trans) galacto-oligosaccharides (GOS), fulfil all the criteria for prebiotic classification (Pokusaeva et al. 2011).

Prebiotics like inulin and pectin exhibit several health benefits comparable to probiotics, such as reducing the prevalence and duration of diarrhea; relief from inflammation and other symptoms associated with IBD; and protective effects to prevent colon cancer (Peña 2007). They are also implicated in enhancing the bioavailability and uptake of minerals, such as magnesium and calcium; lowering of some risk factors of cardiovascular disease; and promoting satiety (Pokusaeva et al. 2011).

An exception for my suggestion of sticking with mainly foods is severe gut issues, such as IBD, or procedures such as a colonoscopy which wipe out a significant amount of the gut microbiome with the Golightly preparation. In this case, I recommend a synbiotics. These refer to food ingredients or dietary supplements combining probiotics and prebiotics in a form of synergism, hence the term synbiotics. The leading brand of synbiotic supplement I trust the most is this one. I also like this brand not only because of its survivability and dedication to continued research but also because it combines strains that have been studied to be effective on different systems beyond digestion, such as cardiovascular.

The health benefits claimed by synbiotics consumption by humans include increased levels of lactobacilli and bifidobacteria and balanced gut microbiota; functional improvement of the liver, which plays a key role in digestion, even in cirrhotic patients; improvement of immunomodulating ability, currently studied in relation to COVID-19; and even prevention of bacterial translocation and reduced incidences of nosocomial infections in surgical patients (Zhang et al. 2010).

I also recommend high-count probiotics or Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG (LGG®), which is the most extensively studied probiotic strain. This is obtained through a healthcare provider and you can discuss supplementation with them in the case of a procedure or severe gut issues. There are also LGG products that are blended with Probiotics, making it a suitable synbiotic.

Eat your fruits and vegetables

While all the different foods that make up your diet can influence the gut microbiome, it is the fiber—the carbohydrates in our diet that we cannot break down ourselves but the bacteria in our gut can use readily— that predominantly drives the formation of a healthy microbiome. Eating a diverse and abundant selection of fruits and vegetables is a great way to feed some of the most health-promoting bacteria in our gut. Aim for lower sugar fruits, such as berries, as bad bacteria can also proliferate more easily feeding on higher amounts of sugar. Bitter greens such as dandelion greens are also optimal as they are beneficial for the liver, which also plays a critical role in digestion. Here’s a recipe that combines bitters and probiotics, if you opt for raw sheep’s cheese or plant-based fermented cheese, such as Kite Hill’s ricotta.

Incorporate Bitters

Bitters, as also mentioned above, work according to research as “the appetite is sharpened because the gustatory nerves are stimulated; this reflexively leads to dilation of the gastric vessels and to an increase in the gastric and salivary secretions.” Pavlov’s research on the autonomic nervous system also strengthened this finding.

Bitters first activate increased saliva production, which assists in digestion as saliva is the first mechanism that starts breaking down food. Bitters can also signal the stomach to release more gastric juice, alleviating heartburn, cramping, and indigestion. Some general bitters are dandelion, gentian, wormwood, bitter melon, and burdock root. This infographic and guide to bitters by our friends at Urban Moonshine is a great example. I also recommend this tincture by our friends at Herb Pharm to assist in liver function and therefore digestion. Take caution with bitters as some people can experience nausea, increased cramping, diarrhea, gas, and sore stomach with consumption. Some of them might also not be safe for people with certain health conditions such as epilepsy, kidney and/or liver disease, low blood pressure, bleeding disorders, or those on blood thinners. You might also be allergic to certain herbs. As mentioned before, discuss with a healthcare provider before starting any regimen.

Add resistant starch

Starches such as bread or pasta are quickly broken down and absorbed by our body. But a fraction of that starch is resistant to digestion and acts more like a fiber, feeding the bacteria in our gut. Resistant starch has been identified as particularly beneficial for supporting all of those healthy functions of the gut microbiome.

Some sources of resistant starch include potatoes and legumes. All sources of starch, even pasta, can also become more resistant after cooking and then cooling in the fridge. Cooking then cooling and adding beneficial fats to these starches increases their gut health-promoting properties. I recommend potatoes cooked then cooled with lots of herbs like dill or parsley, pinch of sea salt, a small dash of gut health-promoting apple cider vinegar, and a good drizzle of high quality olive oil.

Experiment with different fibers

Not all gut microbiomes are the same and not all fibers are the same. Certain fibers and microbiomes will mix better than others, depending on what functions are present. This means that you need to do some experimentation to see what fibers will make you and your gut feel the best. You can do this with fiber supplements or with different categories of fiber sources such as whole grains, legumes or cruciferous vegetables like broccoli. Give your microbiome a couple of weeks to adjust to each fiber source to see how it responds.

Exercise

Regular physical activity is not only good for your heart, it is good for your gut, too. Studies recently showed that some of the lactate produced during exercise can impact certain gut microbes, although we don’t yet know how and why. Start slow if you haven’t had regular physical activity as part of your daily life. Activities such as running, rebounding, or ones that require light jumping motion also aid in lymphatic circulation, which assist in ridding the body of pathogens.

About the Author

Almila Kakinc is the Founder, Editor-in-Chief of The Thirlby. She is also the author of the book The Thirlby: A Field Guide to a Vibrant Mind, Body, & Soul. She earned her Master’s in Nursing as a Dean’s Scholar from Johns Hopkins University and is currently a Labour & Delivery Nurse. Her background is in Anthropology & Literature, which she has further enriched through her Integrative Health Practitioner training at Duke University. She lives in Seattle, WA, where she regularly contributes to various publications. She is a member of Democratic Socialists of America and urges others to join the movement.